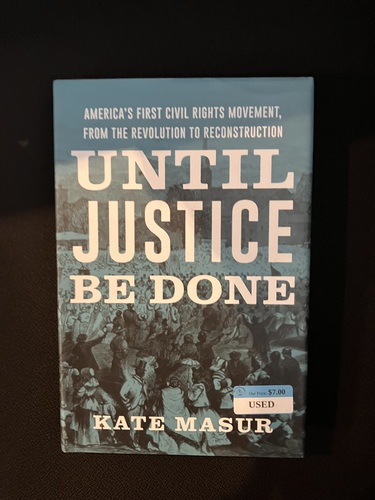

The half-century before the Civil War was beset with conflict over equality as well as freedom. Beginning in 1803,many free states enacted laws that discouraged free African Americans from settling within their boundaries and restricted their rights to testify in courtmove freely from place to placeworkvoteand attend public school. But over timeAfrican American activists and their white alliesoften facing mob violencecourageously built a movement to fight these racist laws. They countered the statesΓÇÖ insistences that states were merely trying to maintain the domestic peace with the equal-rights promises they found in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. They were pastorseditorslawyerspoliticiansship captainsand countless ordinary men and womenand they fought in the pressthe courtsthe state legislaturesand Congressthrough petitioninglobbyingparty politicsand elections. Long stymied by hostile white majorities and unfavorable court decisionsthe movementΓÇÖs ideals became increasingly mainstream in the 1850sparticularly among supporters of the new Republican party. When Congress began rebuilding the nation after the Civil WarRepublicans installed this vision of racial equality in the 1866 Civil Rights Act and the Fourteenth Amendment. These were the landmark achievements of the first civil rights movement. Kate MasurΓÇÖs magisterial history delivers this pathbreaking movement in vivid detail. Activists such as John Jonesa free Black tailor from North Carolina whose opposition to the Illinois ΓÇ£black lawsΓÇ¥ helped make the case for racial equalitydemonstrate the indispensable role of African Americans in shaping the American ideal of equality before the law. Without enforcementpromises of legal equality were not enough. But the antebellum movement laid the foundation for a racial justice tradition that remains vital to this day.